Orion: The Space Flight Simulator

When I was much younger, still on my first computer, my parents gave me a voluminous 240 MB hard drive for my Mac IIcx. Upon connecting the drive, I found among other contents a shareware spaceflight simulator, Orion, the work of one Robert Munafo. This serendipitous acquisition quickly became one of my favorite programs. With this program, one controls a spacecraft by applying thrust, roll, pitch, and yaw, and has a capability to travel to any star system within a 32 light-year radius (all of these helpfully had 9 planets, Pluto being considered a planet at the time). By flying at a planet in just right way and executing some slightly deft maneuvering, one could enter orbit. By executing the maneuver incorrectly, you’d fall into the planet or, more likely, get flung out past escape velocity back into the star system.

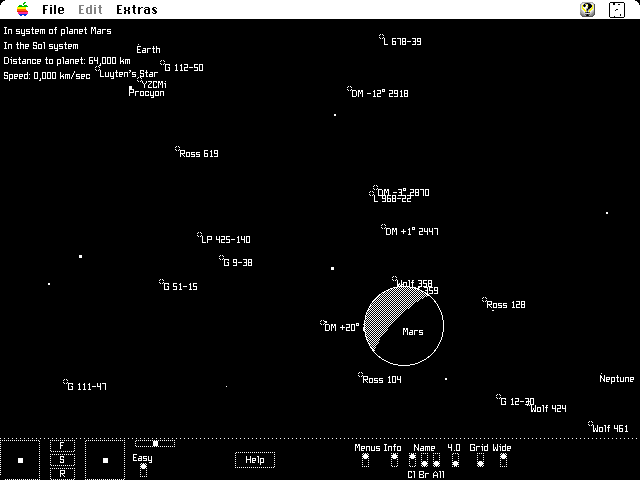

Pictured is a screenshot of Orion’s mighty workings. All controls are shown in the lower ribbon. By modern standards the control system is obtuse, but for 1988 at a time when people were still figuring out how computer interfaces should work, it was quite excellent. One turned the ship by holding the mouse down in the lower left box, with the direction and magnitude of the turn indicated by the offset of the click from the center dot. The F/S/R buttons controlled the motion of the ship, being forward/stop/reverse. The next box allowed one to perform lateral thrust. The top bar allowed one to roll. Then there was a control for easy mode, with non-easy mode resulting in Newtonian motion (once you applied thrust in a direction, turning did not redirect your velocity) and the application of gravity. Remaining controls toggled display elements.

This program was enormously fun and instructive.

First, it gave me a healthy appreciation of the vast scale of the universe. At first blush it may sound like a 32 light-year long leash is not terribly restrictive, but the paucity of “interesting” stars that lie in that sphere soon becomes clear. That limit quickly seems unbearably oppressive. (For example, none of the interesting stars actually in the constellation Orion can be visited within the program Orion. 🙂)

It also gave me an intuitive feel for Kepler’s laws, especially as it applied to elliptical orbits and the inverse relationship between orbital distance and velocity as I flew in orbit around a planet, many many years before I learned that they were called Kepler’s laws. (“Hey, when I’m twice as far away, I’m going half the speed…”)

Quite apart from anything having to do with space and more appealing to my nascent interest in software engineering, seeing my orbital parameters (major/minor axis) slowly change over time when they realistically should not have changed gave me an appreciation for the role approximate arithmetic takes in software simulations of physical systems, and the dangers of accumulated numerical error.

Less intellectually, then, as now, I was a fan of Star Trek TNG and liked to pretend I was flying in the USS Enterprise. The supposedly impossibly fast Warp 9 amounts to a paltry and pitiful 1,516 times the speed of light (roughly 3 AU per second), meaning that a trip from earth to the Alpha Centauri system would take almost exactly 24 hours. My preteen brain found this a sobering and disappointing realization. Nonetheless, I decided to make the trip one day. Pretending my bedroom was a spaceship cabin and my computer the helm (naturally allowances were made to leave the room for the bathroom and food), I set my sights for Rigel Kent and accelerated to Warp 9. During the daylong journey I read, periodically corrected my course, and overnight I slept. Roughly a day later I arrived at Rigel Kent, whereupon I “explored” all the planets. I was oddly proud of myself for completing the journey, but the tedium did give the lie to the notion of Jean Luc Picard and company casually dropping by Earth from the far reaches with the same ease of someone today traveling from New York to Boston.

With the help of Basilisk II, I was able to use Orion once again for the first time in about two decades. Aside from the usual shock I encounter using ancient software — e.g., the old Mac design philosophy of never using keyboard controls, the help box with a snail-mail address and no sign of a @ or .com anywhere, the usual hiccups of software when running on a computer thousands of times the speed of the Soviet era hardware it was designed for — it was quite enjoyable, and wonderfully nostalgic. So, thank you Robert! Sorry I never sent you $7, but my ten year old brain didn’t quite have a fully developed sense of social responsibility.